This is where I put my more technical kind of writing. I also have a more casual blog

If you have a comment feel free to email me at jack dot evoniuk at gmail.

This post assumes you know what logic gates are, but not much more. I wrote it to serve as a quick guide on some very basic facts about logic gates that aren't often justified, and when they are, they're justified in an overcomplicated way. We'll go over are why there are only six binary gates and why only two of them are functionally complete.

Games for the Atari 2600 were quite constrained. When Warren Robinett first pitched the idea that would become Adventure, a game where you would explore a world with many rooms and pick up items to help you along the way, he was denied because it wasn't thought feasible. And it made sense to do so. This was the late 70s; there had never been a game with multiple screens before. This was in the days of Space Invaders and Pac Man, when everything in a game was in front of the player at all times, so the fact that Adventure was able to have 30 rooms when it was finally released in 1980 was quite impressive.

It was quite an innovation to have multiple rooms, and the fact that Adventure managed to have 30 was revolutionary. But Pitfall!, made by David Crane and released in 1983, had 255, all of which were much more elaborate (graphically speaking) than anything in Adventure. In this article we'll talk about how this was done.

If you've ever taken a class on logic you will have learned about contrapositives. A constrapositive of a statement A implies B is not B implies not A. So, for example, if you have the statement "the presence of rain implies the presence of clouds", the contrapositive of that would be "the absence of clouds implies the absence of rain". What's important about contrapositives is that they're logically equivalent to the original statement. That is, they mean the exact same thing.

The title you see above is commonly cited as the contrapositive of the popular saying "whatever doesn't kill you makes you stronger". But it doesn't seem equivalent, and I'm here to argue that it's not.

In the Nand to Tetris course you have to do many things. It's quite a fun course. In project 8 you implement a compiler from VM code into assembly code. Most of the compiler is straightforward, but there's one part that requires a clever trick, one sufficiently interesting to make me want to write about it.

I have a guilty pleasure of visiting websites of professors. Their, um... minimal design brings me back to when I first went online in the early 2000s. Their aesthetic, or lack thereof, inspires nostalgia, but at the same time, is, well, really bad. Text going to the edge of the screen, Times New Roman, microscopic line height, pure blue links... it's a sight to behold. But because of this the sites have instantaneous loading times, and free up the professor to make some amazing content.

There's been an equation on my mind lately, that goes something like this:

information = data + interpretation

It's a pretty simple idea, but it's one that has helped me organize my thoughts on many occasions and sort through complicated topics more easily. This isn't going to be a very focused article, but rather a collection of ideas that have crossed my mind lately, which I'll attempt to use in order to show the usefulness of the above equation.

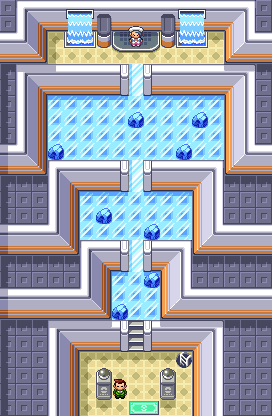

In the final gym in Pokemon Ruby and Sapphire there is a puzzle you have to solve before being able to challenge Wallace. It is arranged like so:

To solve it, you have to step on each block of ice exactly once in each of the three sections. Not only that, but the final block you stepped on in each section had to be the one situated before the ice slide. Once all the squares were stepped on in a section the ice slide would turn into stairs, allowing you access to the next section of the puzzle, and finally Gym Leader Wallace.

In this article we'll come up with a way to program to solve this puzzle, and all puzzles like it, with about 60 lines of JavaScript.

It has been assumed, by mathematicians and laymen alike, that if something were true it could be proven. In 1931 Kurt Gödel showed this assumption to be mistaken. Gödel first published this result in a short paper titled “On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems” as a response to questions that had arose about uncertainties in the foundations of mathematics. Gödel showed that such uncertainties in mathematics are inexorable and in so doing forever changed perceptions of mathematics, reasoning, and philosophy.

This is a discussion about forming gradients through color spaces, a gradient being a smooth transition between two colors. RGB and HSL will be the focus, but much will be able to be extrapolated to other spaces. In part 1 we define the RGB and HSL color space. In part 2 we discuss what a gradient is and how to define it mathematically. In part 3, as a bit of fun, we will define an alternative way of forming gradients in HSL space.

There comes, in life, certain times when good, God-fearing Americans encounter such bafflingly stupid arguments that they are compelled by their most inner sense of justice to respond. I recently read How to Really Pronounce GIF, an argument by Aaron Bazinet, and this is one of those times.

The first thing that needs to be said is that mathematical objects aren't real. At least, they're not real like you and I. Mathematical truths and objects “exist” entirely due to definitions and the logic that ties them together. The reason why .999... is equal to one is entirely due to the way we define what it means for a decimal to repeat.

The algorithm (given in C) for the nth fibonacci number is this:

int fibonacci(int n) { if (n == 1 || n == 2) return 1; return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2); }

It's simple enough, but the runtime complexity isn't entirely obvious. An initial assumption might be that it is O(2n), as it is a recursive formula that branches twice each call, but this isn't the best upper-bound.

The 10th edition of the ECMA specification of JavaScript required that the Array.sort method be stable. Here I want to have a deeper discussion as to what sorting and stability mean from a formal, mathematical perspective, in addition to discussing the ramifications of the change.